Dyke Drama

The Enduring Power of Lesbian Theater

Lillian Hellman’s controversial 1934 play The Children’s Hour—about two female teachers at a private girls’ school and the lesbian rumor that destroys their reputations—concluded with one of the lead characters committing suicide. Though shocking, this ending was not surprising to audiences: it was common for the handful of lesbian characters in mainstream plays throughout most of the 20th century.

Accordingly, lesbian playwrights, actors and audiences found few positive portrayals of themselves on stage. It was not until the 1960s that a community of lesbian theater artists were able to write and produce work that explored feminism and gender roles, a scene that coincided with movements to further the civil rights of African-Americans, women and gays. Rather than wait for mainstream theater to catch up with the times, radical female playwrights and actors created what they wanted to see on stage.

Innovation in lesbian theater accelerated in tandem with another movement—the New York art scene of the 1980s, in which several of today’s most prominent lesbian theater artists got their start. Despite the culture war mentality of the 1990s and the recession of the 2000s, lesbian theater continues to thrive on creativity and fearlessness.

IT CAME FROM DOWNTOWN

The social revolutions of the 1960s extended from college campuses to the theater, encouraging an off-off-Broadway scene amenable to new works. Smaller venues and independent companies began producing radical plays about gender, feminism and sexuality, among other formerly taboo topics, bringing forth the first wave of important lesbian playwrights.

Megan Terry, called by some the mother of American feminist drama, wrote Viet Rock: A Folk War Movie (1966), the first rock musical as well as the first drama about the Vietnam conflict. She won an Obie for Best Play in 1970 with Approaching Simone: A Drama in Two Acts. Her 1974 work Babes in the Bighouse: A Documentary Fantasy Musical About Life Inside a Women’s Prison further explored sexuality, feminism and the degradation of women.

Cuban-born playwright Maria Irene Fornes, winner of the New York Innovative Theatre’s Lifetime Achievement Award, began her career with Tango Palace in 1963, then won 13 Obies throughout the 1970s. Fornes remains an integral figure in American theater as a playwright and teacher.

Jane Chambers’ 1980 drama Last Summer at Bluefish Cove, featured in the first Gay American Arts Festival in New York, drew both criticism and praise in the mainstream media for depicting the lives of a circle of lesbian friends at a summer retreat. (Spoiler alert: A lesbian still died at the end.)

The 1980s might be considered the golden age of lesbian theater: groundbreaking playwrights worked in the vibrant milieu of downtown Manhattan’s art scene. They performed in unconventional venues and on the street in addition to theaters. Collective theater companies and venues emerged to produce the new lesbian plays, and a distinctive downtown aesthetic grew among artists and venues that differentiated them from their traditional uptown counterparts.

In New York, Peggy Shaw and Lois Weaver (who, along with Deb Margolin, formed their company Split Britches) founded the WOW Café Theater as a lesbian theater festival in 1980, then made the company a permanent collective. Performance spaces like WOW gave lesbian artists the chance to develop new theatrical styles and address issues that weren’t often seen uptown, and as a result, WOW became an incubator for most of the major names in lesbian (and American) theater in the 1980s.

Dixon Place, founded in 1986 by Ellie Covan, adopted a similar mission and became a lab for workshopping new performance pieces, especially those by women, LGBT people and artists of color.

Plays, though, weren‘t confined to actual theaters; shows took place in nightclubs and art galleries. “My first show was at the Pyramid Club at 2am in 1979,” says playwright and novelist Sarah Schulman. “For the next 15 years I worked as part of the Downtown Arts Movement, working in the newly evolving forms and content of the 1980s and early ‘90s. I did 15 shows during those years.”

Moe Angelos, a founding member of the theater group Five Lesbian Brothers, remembers, “I wandered into the WOW Festival in 1981, became an irritating 20-year-old fixture and then my education truly began. Early on, I pretty much realized that the range in conventional theater was going to be limited. I’d rather go to all the trouble of making my own play than trying to get in a production that maybe I’m not so crazy about the content of in the first place.”

Angelos, along with Babs Davy, Dominique Dibbell, Peg Healy and Lisa Kron as the Five Lesbian Brothers, played with the traditional form and stereotypes of drama and its depiction of lesbians. Their plays Voyage to Lesbos, Brave Smiles, The Secretaries and Brides of the Moon won audiences and influenced the next wave of downtown theater.

But the world outside the theater was changing fast. In the 1990s, an economic boom and ensuing gentrification robbed communities of their performance spaces. The so-called culture wars pitted radical artists like lesbian playwright/performer Holly Hughes against the government’s National Endowment for the Arts; Hughes lost her NEA grant after conservative members of Congress disagreed with her work. The NEA itself lost much of its funding, and artists suffered.

“By 1994, my community had been destroyed by AIDS, gentrification and MFA programs,” Schulman says. “I decided to become an ‘uptown’ playwright. My first uptown production was at Playwrights Horizons in 2002. Since then I have worked exclusively in off-Broadway and major regional theaters.”

Fortunately, some of the downtown playwrights found the mainstream more accepting in the late 1990s. Lisa Kron of Five Lesbian Brothers produced solo work off-Broadway and regionally. In 2006, Kron’s Well went onto Broadway. Lesbian theater pioneers are now teaching the next generation (Kron at Yale, Holly Hughes at the University of Michigan, and Schulman in the City University of New York, among many others). Paula Vogel, who won the Pulitzer Prize for her play How I Learned to Drive, is the head of the playwriting program at Yale, after having turned out some of the major emerging playwrights at Brown.

NEW YORK AND BEYOND: EXPLORING LESBIAN LIVES

Playwrights today—in dramas, comedies and solo work—are building on the radical stories of lesbian identity first touched upon in the 1960s, though some still find obstacles in their road toward mainstream respect.

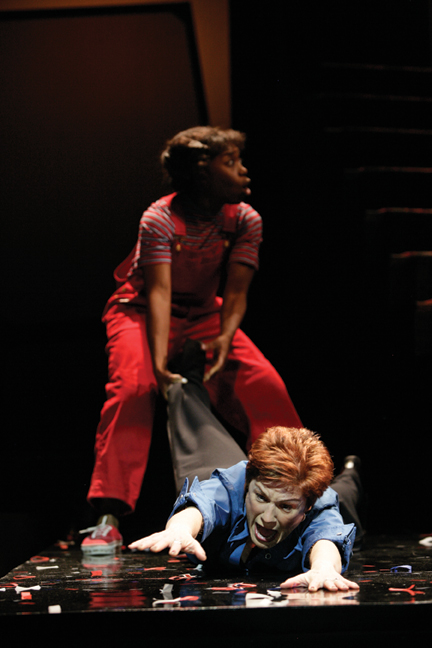

Actor, playwright and newly-appointed Artistic Director of the Coyote REP theater company Donnetta Lavinia Grays’ solo show, the cowboy is dying, was a coming-of-age comedy about being a black Southern lesbian falling in and dealing with love. “I truly understood what it meant to create theatre after I was cast in Well on Broadway,” Grays says. “I was an understudy and got to watch Lisa Kron and [director] Leigh Silverman shape and reshape elements of the show day in and day out. Leigh and Lisa also serve as advisors to Coyote REP. I have learned not to fear setting up an image or idea and how to follow through with that vision from both of these women.”

Within the mainstream, Grays asserts, “the image of African-Americans on stage doesn’t reflect our own intra-cultural diversity. As a writer, I wish to at least reflect the truth in who I see in the mirror and have audience get that black folks exists outside of a set of preconceived notions.”

KS Stevens also creates her own work based on what she doesn’t see. Her play Butch Mamas!, a comedy exploring butch-to-butch attraction, butches who want babies and “butch chasers,” premiered in September at WOW. “The best medium for me to convey my stories is through theater,” she says. “I consider myself a playwright, but in order to put a crew together I also have to be a producer and get other professionals excited enough to work on my productions.“

She adds, “I wrote Butch Mamas! for my friends and my communities because I wanted to put a spotlight on a diverse group of butch lesbians, our friendships, and relationships to each other.”

Stevens’s other work includes Yellow Lens, an evening of Asian-American one-act plays, which she personally produced at WOW.

A historically accurate lesbian relationship is at the heart of playwright Vanda’s Lambda Literary Award-nominated play Vile Affections. First presented in the NY Fringe, Vile Affections tells the story of one of the first recorded lesbian relationships between two nuns in an Italian convent in the 1500s—presenting a heretofore unknown piece of lesbian history. Vanda’s other play, Why’d Ya Make Me Wear That Joe?, about two “girls left behind” during World War II who fall in love, premiered at the Fresh Fruit Festival in New York and has appeared regionally in Los Angeles and Chicago.

Carolyn Gage, who won the Lambda Literary Award in Drama last year for a collection of her plays, says her career took off when she filed a lawsuit against the university where she had a doctoral fellowship. “I was a whistleblower on a credit scandal, and it turned into a huge witch hunt. During this time I wrote a play about Joan of Arc (I could identify!) and I am still touring in it twenty years later,” she says.

“My experience with that lawsuit really shoved me out of the mainstream, and I was coming out as a lesbian at the same time and recovering memories of childhood abuse. I began to tell empowering stories about lesbians and especially about survivors of child abuse. These stories are mostly absent from the mainstream, and so I have spent most of my career in lesbian communities and communities of feminist activists. What a blessing!”

Her solo shows also include The Last Reading of Charlotte Cushman, Amy Lowell in her Own Words, and Extravagant Love: the Life of Violette LeDuc. Gage also wrote The Countess and the Lesbians after she toured Kilmainham Gaol in Ireland, where many of the Irish leaders of the 1916 Revolution were imprisoned and executed. Her plays are frequently performed by lesbian theater companies around the world.

Another Lambda Literary Award winner (for her book bull-jean stories), Sharon Bridgforth is the Artist-in-Residence in Performance Studies at Northwestern University. Bridgforth describes herself as “a writer whose work lives in the theatrical jazz aesthetic. A lineage of artists that preceded me have broken ground, busted doors wide open in the field. A little of what is assumed in this aesthetic is that art and life are not separate; that making art is a communal process; that visual art, movement, music, dramatic interpretation, poetic voice, ritual, prayer and the human spirit are presented simultaneously to make the work come alive.”

Bridgforth spent the majority of her career in Austin, Texas, where in 1992 she founded The Root Wy’mn Theatre Company. In 1999 she began pursuing solo projects. On November 20 and 21 in Chicago, she will perform a reading of delta dandi, a new “queer/of African descent/woman-centered piece about Spirit.” “delta dandi looks at the transmigration of one Spirit’s many lives and asks, what must a soul do to heal, and what is the traditional role of queers in ritual?” Bridgforth says.

Elizabeth Whitney’s Wonder Woman! A Cabaret of Heroic Proportions! also opens this fall at Emerging Artists Theatre’s Fall EATfest, after a sold-out run at the International Dublin Gay Theatre Festival this summer. In Whitney’s show, Wonder Woman reinvents herself as a karaoke lounge singer and tells the truth about her life on Paradise Island—among other things. Whitney’s next piece, A Day Without Sunshine, is inspired by anti-gay former orange juice spokeswoman Anita Bryant, which she workshopped at Dixon Place and which TOSOS Theater (The Other Side of Silence, a NYC LGBT theater) will produce in Spring 2010. “It’s all original music, and my intention with the show is to humanize Bryant and to explore conservative women in positions of power who aren’t feminists. It’s a very thoughtful piece, though true to my signature style, quite playful as well,” Whitney says.

If you write it they will come: that’s the message that has fueled Meryl Cohn’s playwriting career over the last decade. Cohn’s award-winning plays, first produced by the Provincetown Theater, now by Counter-Productions, have become a highlight of Women’s Week. “Once I finished the MFA, I didn’t write another play for many years,” Cohn says. “Eventually I joined a playwrights lab in Provincetown.” Cohn has helped start a playwrights’ lab in Northampton, where she spends part of the year, to help other writers tell their stories and find their voices.

Cohn’s plays are generally comedies, featuring strong women characters, many of them lesbians, with a humorous take on serious issues. In And Sophie Comes Too, a lesbian wants to adopt a baby, but has to closet herself to a nosy social worker; in Almost Home, a woman has to figure out who she is in the life of her ex’s daughter; in The Siegels of Montauk, the widow and daughters of a disgraced doctor have to figure out how what he did will change their lives.

Cohn also wrote the upcoming musical Insatiable Hunger with music and lyrics by Susan Goldberg and Billy Hough. It stars Lea DeLaria, who plays a washed-up rock star who has a chance to redeem herself with the family she abandoned long ago.

Tara Ayers is the artistic director of StageQ, Queer Community/Theater in Madison, Wis., whose mission is to produce quality queer-themed theater and community. In 1974, Ayers came out into a radical lesbian feminist community in Kansas City, MO, “in the excitement of the civil rights, anti-war and early women’s liberation movements. Radical lesbians knew that the world was a mess and that we had (or could develop) the tools and analysis to transform it,” she remembers. Ayers produced and performed women’s music, and eventually channeled her activism into the theater with the comedy improv troupe Flaming Dykasaurus. She took over as Artistic Director of StageQ in 2005, where this season’s offerings feature a production of Carolyn Gage’s Sappho in Love.

Multitalented Lou Clark is a playwright, director, producer, actor, and educator in Albuquerque, NM where her work reaches a wide LGBT-inclusive audience. Clark is also the Artistic Director of two theater companies. The first, Ka-HOOTZ, is dedicated to supporting local playwrights and producing work by living writers, including Clark’s own The Politics Of Hair. With Brynne Badeaux, Clark founded the second company, Solarity, at VSA North Fourth Art Center in Albuquerque and is comprised of members with and without disabilities. “I tend to identify with what mainstream America would say are minority people or voices,” Clark said. “Part of the reason is definitely because I am a lesbian, but another reason is that I lost my father to a tragic, untimely death when he was 43 and I was 9. At a very early age I understood what it felt like to be different. That’s why my work often draws me outside of the mainstream, though I’m comfortable in the mainstream as well.”

Joan Lipkin is the artistic director of That Uppity Theatre in St. Louis, MO, and describes herself as a “playwright, director, educator, social critic and cultural provocateur.” Lipkin works in a town known as a conservative stronghold, and that attitude prompted her latest play, Beyond Stonewall: Why We March. With co-author Sharon Bandy, in conjunction with a local organization called Show Me No Hate, they created a Facebook page with the script, a sample poster, press release, articles about the play and a video.

“I became interested in writing something when the St. Louis Post-Dispatch wrote an article about the new face of gay activism and it spawned almost 400 reader comments, mostly negative,” Lipkin says. “The play has some of those comments. It also has the ghosts of Stonewall, a disgruntled news reporter, college students and a confrontation between a white gay male bank president and an African American lesbian activist.”

CHALLENGES REMAIN FOR LESBIAN PLAYWRIGHTS

Getting new work of any kind produced isn’t easy for emerging playwrights, Vanda asserts, and the difficulties multiply when the work involves lesbian characters and stories.

“One of the most painful things for me in the theater, whether it is mainstream, gay or women’s theater, is that it is extremely difficult to bring in audience to see new work and it may be doubly difficult to bring in audience to see new women’s work,” she says. “The myths I’ve had to dispel have been more individual than institutional. I’ve had to explain to various individuals that just because a play might revolve around lesbian characters, that does not mean the purpose of the play is to bash men. I pride myself on writing full-blown male and female characters with depth.”

Andrea Lepcio, whose play Looking for the Pony received an acclaimed Off-Broadway production last season and a regional production in Atlanta, says she also feels the “women’s work” label still applies.

“I hate that being a woman matters,” says Lepcio, who also coordinates the Dramatists Guild Fellowships designed to launch emerging playwrights into professional careers. “I feel like I’ve waited my whole life to be treated as a human being. Within that, I hate that all the sexist feelings that people have can influence how a play might be read: the classic problem that men are universal and women are women. I do my best to put women in general and lesbians in particular on the stage in exciting, unexpected and highly theatrical ways. I doggedly trust that if the writing is good enough, I’ll break through and find my audience.”

Grays adds, “The myths of women’s theater is that there is no action; that it is touchy feely, soft-focused in its core; not funny, and when it is angry, it is geared toward men,” says Grays. “Oh, and that a play written by a woman isn’t profitable. As women become more and more the mainstream gatekeepers, I’m afraid that women in the theater may be in the driver’s seat of perpetuating these stereotypes.”

“The most destructive ethic in mainstream theater is that familiarity equals quality,” Schulman says. “They think that work that repeats what is already known is good, and work that expands what is already known is wrong or badly written.”

“I wish that there were more old school arts-focused producers,” Bridgforth says. “That more resources were given to nurturing vision, the development of new works and to providing full productions for the works once they are developed. If producers truly engaged with and invested in community involvement, if they extended more trust to the artist they work with, they would never not have audiences. And we would all reap the benefits of innovation and rigor.”

Angelos has a slightly different take on the subject. “In the mainstream theater, I guess I’d have to say that there is still a painful dearth of girl-on-girl action. There are lesbians in plays nowadays, but please, can we have some hot lesbians who are sexual and like to make out? Not to objectify dykes completely, but I would vote for a more public displays of sexuality.”

Perhaps the theater will never meet every need of its lesbian artists, but its limitations don’t scare off groundbreaking new playwrights and actors: today’s thespians relish the challenge of creating art in a sometimes hostile environment. Bluefish Cove author Jane Chambers told the New York Times in 1981 that ”growing up female in this country and wanting to be a playwright” was her biggest frustration. ”When I went to college,” she said, ”women were not allowed in the playwriting or directing courses unless there were seats left over after the men signed up.”

Thirty years later, queer artists start their own companies, lesbians find representation in many more facets of the mainstream commercial and non-profit theater, new queer work is produced all over the country—and the spirit of exploration and ingenuity is as strong as ever.

FALL’S LINEUP OF LESBIAN THESPIANS

Acclaimed playwright Lucy Thurber’s new play Killers and Other Family runs through mid-October at the off-Broadway Rattlestick Playwrights Theater.

Another season of the live lesbian soap opera Room For Cream will run on weekends at Ellen Stewart’s club at La MaMa in 2010, after Theatre of a Two-Headed Calf’s Dyke Division took it on the road to Istanbul this summer.

Sarah Schulman is working on two projects simultaneously: Shimmer, a musical with score by Anthony Davis and lyrics by Michael Korie, is adapted from her novel The Lady Hamlet; another project, Enemies, A Love Story (adapted from I.B. Singer) will be read at Theater J in Washington, D.C. this fall.

Lou Clark is directing Reflections by Solarity that opens November 13 in Albuquerque, NM.

Andrea Lepcio is working on a new two-character “absurdist lesbian romantic comedy.”

Donnetta Lavinia Grays is writing The New Normal, a play based on the blog of her friend Anna Warren Schumacher who was diagnosed with breast cancer at age 32, six months after her son was born.

Carolyn Gage is working on a play about Lizzie Borden’s maid, and a play about the founders of post-modernism, who were both pro-pedophilia activists. “I don’t think very many folks realize that, or the implications of it,” she says.

KS Stevens is looking for another venue for Butch Mamas!, and will be Miss Butch Mama, in the Miss Lez Pageant 2009, hosted by Murray Hill on October 11 in New York City.

Moe Angelos is in Continuous City with The Builders Association, which creates original productions based on stories drawn from contemporary life.